The Luvale (also spelled Lovale, Lubale, Luena or Lwena) are a Bantu?speaking people in southeastern Angola (especially the Moxico Province) and into northwestern Zambia. Their primary language is Luvale (Chiluvale), which is part of the Chokwe?Luchazi subgroup of Bantu languages. It uses a Latin alphabet and is recognized in Zambia as a regional language; in Angola, the language is used in homes and between communities.

Historically, the Luvale share cultural, historical, and linguistic ties with the Lunda, Ndembu, Chokwe, and Luchazi peoples. The Luvale have long been under some influence from the Lunda states, and trade routes in the 19th century—including trades in ivory and other goods—connected Luvale territory to Chokwe and other neighboring polities. Their identity has been shaped in part by these connections and by interactions and sometimes conflicts with neighboring groups.

Luvale people are primarily rural, living in villages or small settlements in Angola's eastern provinces. Their economy is agrarian: they cultivate staple crops such as cassava (manioc), maize, yams, peanuts, and also grow some crops for market. Animal husbandry (small livestock like goats, chickens) is practiced, and hunting or gathering supplement diets and livelihoods.

Social organization among the Luvale is clan? and lineage?based, with matrilineal descent being important. Chiefs or local leaders (often inherited through maternal lines) govern villages in consultation with councils of elders and ritual specialists. Extended family ties are strong, and respect for elders, communal cooperation, and traditional authority remain significant in daily life.

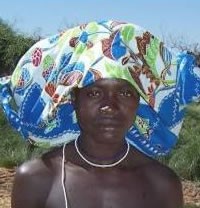

Culturally, the Luvale are well known for artistic traditions—including making baskets, weaving mats, metalwork, pottery, wooden stools, and masks. The "makishi" masquerade tradition (mask dances) connected to initiation rites (such as mukanda) is an important cultural event, even celebrated in festivals. These arts are not only for utilitarian or decorative purposes, but deeply tied to spiritual, social, and moral identity.

Education, health care, infrastructure and access to services are more limited in more remote areas. Portuguese is the national language and is used in formal contexts; Luvale is strong locally, but younger people may be bilingual or use Portuguese for school or business. Migration for work (to towns, mines, labor centers) is part of life, especially when local subsistence is challenging.

The Luvale traditionally believe in a supreme creation god called Kalunga, who is regarded as the highest power, creator of sky and earth, overseeing both the living and the dead.

In addition to Kalunga, they believe in ancestral spirits and in nature spirits ("mahamba") that are part of daily spiritual life. These spirits may be linked to individual, family, or community, and are thought to bring blessings or misfortune depending on how they are honored or neglected.

Illness, misfortune, or disasters are often interpreted as spiritual in origin. Diviners (nganga) or ritual specialists are consulted to uncover the cause of spiritual disturbance. Practices of divination (including basket divination), offerings, rituals, and participation in secret societies or initiation rites are used to maintain harmony with spiritual forces.

Christianity has made inroads among the Luvale, particularly in Zambia; in Angola many Luvale identify as Christian (often in forms that coexist with traditional beliefs). There is blending (syncretism) in some communities, and many still hold traditional rituals alongside Christian forms.

The Luvale people require deeper discipleship that thoughtfully engages both their Christian faith and traditional worldview, enabling them to discern which aspects of their culture align with biblical teachings and which may conflict, so that they can live out their faith with integrity.

Additionally, indigenous Christian leadership is essential; pastors, teachers, and evangelists from among the Luvale who understand their language, culture, ritual practices, and spiritual fears are needed to lead churches that are both rooted and credible. They also need support to break free from spiritual oppression caused by fears tied to ancestral obligations, witchcraft accusations, sorcery, evil spirits, and the influence of customary diviners, which often inhibit openness to the gospel.

Improved access to education, health services, and infrastructure like roads, clean water, and clinics is equally important, as physical hardship often hinders spiritual growth and church maturity.

Let us pray earnestly that the Luvale people experience a deep and genuine spiritual awakening—one that moves beyond cultural Christianity into a vibrant, living faith in Christ.

May they be delivered from fear of spirits, witchcraft, and ancestral demands that bind the heart, finding true freedom and peace in Jesus.

Pray that the Luvale believers would embrace the Great Commission and boldly spread the gospel to every nation, tribe, people, and tongue.

We ask God to raise up strong, compassionate Luvale leaders who are both spiritually grounded and culturally sensitive, shepherding their communities with wisdom and grace, teaching God's word.

Pray for culturally relevant gospel music.

Let churches among the Luvale become safe havens of refuge, healing, and hope, where believers can gather to be nurtured in faith and empowered to reach others.

Pray for unity among the various Christian groups, that denominational walls crumble and believers join together in a shared mission of love and outreach.

Scripture Prayers for the Luvale in Zambia.

Britannica: Luvale people, Culture, Language & Traditions — https://www.britannica.com/topic/Luvale

Wikipedia: Luvale language — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luvale_language

101 Last Tribes: Luvale people profile — https://www.101lasttribes.com

| Profile Source: Joshua Project |